Text By: Diego Hadis

George McCracken: Studies Lines Fragments

Often enough, in contemporary art, the beautiful is considered suspect.

That’s particularly true in painting, where the degree to which a piece is pleasing to the eye—and thus, by implication, not subservient to the ideas behind it—can become a measure of how much we allow ourselves to be taken in by it.

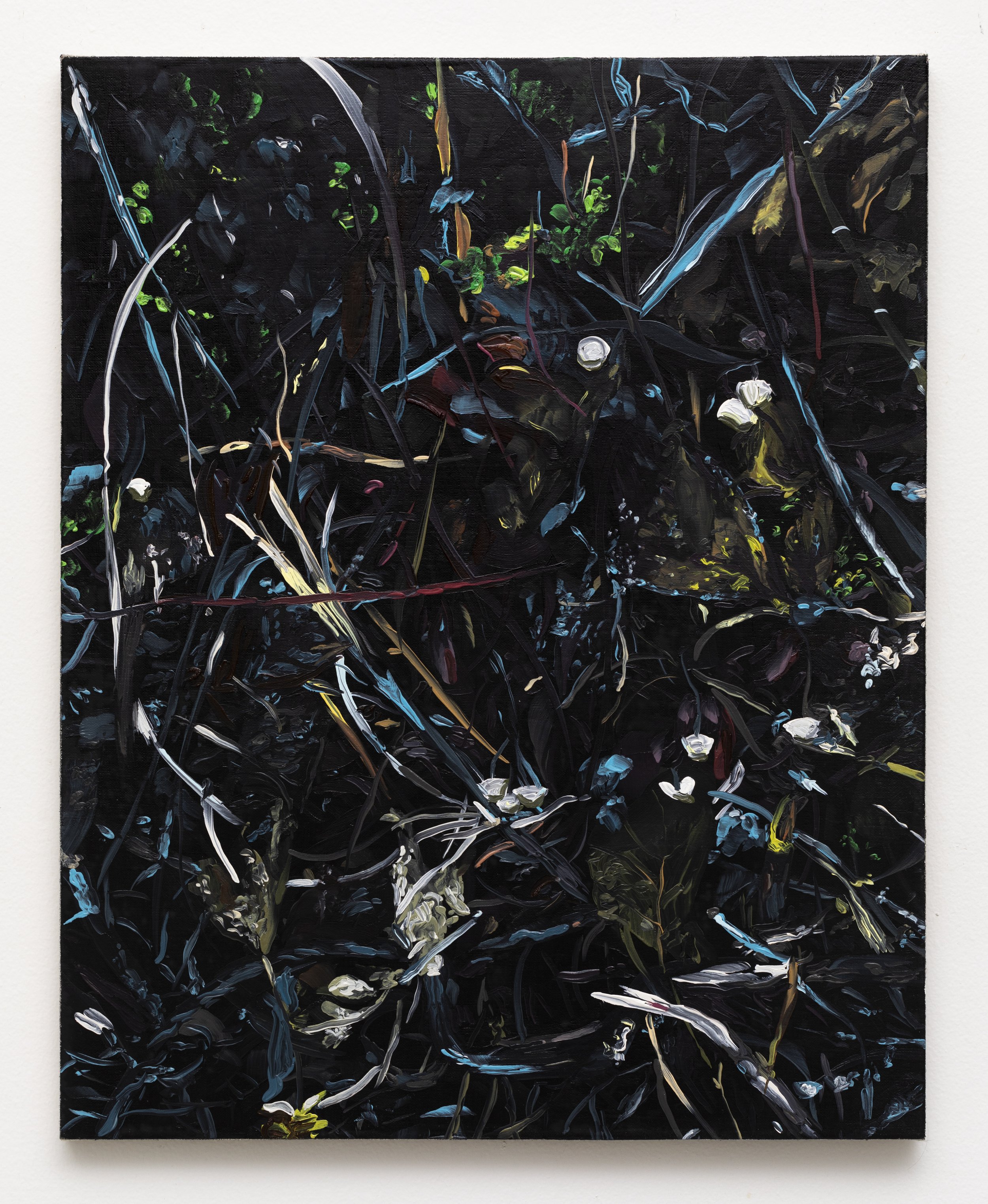

But as the oils on canvas in George McCracken’s “Studies, Lines, Fragments” attest, things need not be that simple. Though the sixteen paintings in the exhibition offer aesthetic pleasures—each is a close-up look at unkempt weeds, and based on pictures he took along the edges of hiking trails—the beauty of the quotidian that they portray is almost secondary to how he made them.

McCracken completed each painting in a six-to-eight-hour session, in which he devoted the first three or four hours to mixing colors. Because he was layering on top of wet black paint, the artist notes, there was a time pressure to complete each canvas before the background could dry. This forced him to be as efficient as possible in his process.

It’s this method, and the compressed time frame, he says, that allowed him to be more gestural in these works. “I try not to do any blending,” he adds. “Every stroke is going to be its own discrete shape defined by the brush.”

McCracken likens his approach to calligraphy. Coincidentally, this recalls a passage in Brian Eno’s diary “A Year With Swollen Appendices” (1996/2021), in which the musician posits a creative strategy: “My ideal is probably based on that story I heard years ago of how the Japanese calligraphers used to work—a whole day spent grinding inks and preparing brushes and paper, and then, as the sun begins to go down, a single burst of fast and inspired action.”

In making the body of work in “Studies, Lines, Fragments,” McCracken says, “I was trying to find abstraction through observational painting and photography. It was a way of allowing myself to do something representational.” The tension between those extremes lets the paintings in the show ride an uncomfortable line between formalism and abstraction. “There’s a coldness to them,” he says. “They really fall apart when you get up close.”

McCracken believes he was best able to achieve these qualities by focusing on the flora that became his chosen subject. “When you paint a face, you can’t escape it,” the artist says. “But when you paint grass, it can be pretty abstract.”